|

I’d like to draw your attention to a new study on Illicit Trade in Fake Pharmaceuticals. It was published today by the OECD Task Force on Countering Illicit Trade (TF-CIT) and the European Union Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO). It shows that international trade in counterfeit pharmaceuticals reached USD 4.4 billion, representing 2.2 % of trade in pharmaceuticals. The report arrives at a particularly disquieting, yet very relevant time. In the midst of people taking extreme steps to stay safe from the Covid-19 virus, we are being exposed to waves of counterfeit and falsified Covid-19 masks, hydro alcoholic gels, testing kits and possible treatments.

This is an upsetting example of the extreme steps counterfeiters will take to profit from the misfortune of others. And it is an urgent reminder that governments must step up enforcement against illicit pharmaceuticals. The OECD and EUIPO report certainly presents a compelling imperative to protect patients, healthcare systems and the wider society from the negative impacts of ingesting substandard, falsified, unregistered and unlicensed medical products. With this body of work, policymakers now understand the nature and scale, the size and scope, the shock and horror of illicit trade. But is OECD willing to follow up by evidencing a strong international policy framework that will provide meaningful tools to governments—inside and outside OECD—to help them clamp down on illicit trade in pharmaceuticals? TRACIT thinks that it is incumbent on the OECD Task Force to Counter Illicit Trade to identify, analyze and disseminate effective policy and good practices to assist OECD member states to better regulate illicit trade in pharmaceuticals. This is fully consistent with the organization’s mandate to design and promote good practices in public policies, to identify the governance gaps that facilitate illicit trade, and to reduce and deter illicit trafficking and smuggling. The OECD’s quantitative studies are extremely useful, but now is the time for OECD to demonstrate the policy leadership that it’s renowned for. Whether it’s the horror of falsified anti-malaria medicines or today’s fake, governments inside and outside OECD are hungry for effective public policies, and the task force has an important opportunity to fill this gap by mapping the best of the best and helping us close governance gaps that foster illicit trade. Jeffrey Hardy Director-General, TRACIT This post was originally published in the Myanmar Times Despite the importance of international trade as an enginefor economic growth, development and poverty reduction, very little attention has been given to the substantial negative impacts of illicit trade. From smuggling, counterfeiting and tax evasion, to the illegal sale or possession of goods,services, humans and wildlife, illicit trade is compromising the attainment of economic and social development goals in significant ways, crowding out legitimate economic activity, depriving governments of revenues for investment in vital public services, dislocating millions of legitimate jobs and causing irreversible damage to ecosystems and human lives. In Myanmar, illicit trade is a major and multifaceted problem. From illegal logging and mining of gemstones like Jade, to alcohol smuggling, wildlife trafficking and counterfeiting of all types of consumer goods, the country faces numerous challenges with combatting illicit trade.In fact, our 2018 Global Illicit Trade Environment Indexranked Myanmar82nd of 84 countries evaluated on the extent they enable or prevent illicit trade. Given the scale of the problem, I was pleased to learn that EuroCham Myanmar had established an Anti-Illicit Trade Advisory Group to fight illicit trade and intensify partnership with the Government of Myanmar.Naturally, I readily accepted their invitation to participate in the Anti-Illicit Trade Forum they hosted in Nay Pyi Taw last September. I considered these to be fundamentally important commitments in the fight against illicit trade, signaling the readiness of business to partner with government in the process. One year later, I have the impression that progress is underway in Myanmar. I think the government is listening to our calls for an effective policy response to illicit trade, and I think they are responding to the recommendations we put forward in Nay Pyi Taw to increasecollaboration with the private sector, raise awareness and establish an interagency task force with high-level authority within the Union Government Office. Consequently, the recent formation of the Illegal Trade Eradication Steering Committee, led by Myanmar Vice President U Myint Swe shows that the Government is taking this issue seriously through both political commitment and implementation. However, if the Steering Committee is going to be effective, the Vice President must exercise his authority and allocate the necessary financial and personnel resources to drive implementation of enforcement measures. It will be the responsibility of the Vice President to ensure that the 13 tasks delineated by the Steering Committee in June become priorities tomorrow. In the balance lies the future of sustainable development in Myanmar. Illicit trade has far reaching consequences, with negative impacts on all aspects of society. Our recent TRACIT report, Mapping the Impact of Illicit Trade on the Sustainable Development Goals, shows how illicit trade in all its forms present significant deterrence to all 17 of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) – holding back progress, increasing costs and pushing achievement of the goals further away. So, the time to act is now. The sweeping, negative impacts of illicit trade on Myanmar’s economic development will require sustained efforts from all stakeholders to achieve an effective response to this varied illegal activity. This year’s 2019 EuroCham Anti-Illicit Trade Forum is a critical opportunity to keep the momentum going. In particular, I hope that EuroCham Myanmar’s Anti-Illicit Trade Advisory Group and the Illegal Trade Eradication Steering Committee can agree on priorities, establish methods of collaboration and work together to implement measures to stop illicit trade in Myanmar. EuroCham Myanmar will host the 2nd edition of the Anti-Illicit Trade forum in Nay Pyi Taw on the 19th September. This event is meant to assess the Anti-Illicit Trade societal and environmental impacts and its perspectives; An exhibition of counterfeit and smuggled goods alongside discussions will strive to improve the knowledge and understanding of the regulatory environment and economic circumstances that enable illicit trade and provide recommendations on priority areas. Jeffrey Hardy Director-General, TRACIT Marc de la Fouchardiere Executive Director, European Chamber of Commerce in Myanmar In 2015, G7 leaders joined more than 150 other world leaders to formally adopt the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and its 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The SDGs have emerged as the blueprint for achieving sustainable development and cover everything from poverty eradication and zero hunger to clean water, decent jobs and peace. Since coming into effect in January 2016, governments, private sector and civil society have rallied around the SDGs to guide policy, implement investment strategies and allocate funding. But while the 2030 Agenda is clear in recognizing that trade will be an important means to achieving the SDGs, little attention has been given to the illicit side of the trade ledger. This is a crucial oversight because illicit trade significantly compromises achievement of the SDGs by crowding out legitimate economic activity, depriving governments of revenues for investment in vital public services, dislocating hundreds of thousands of legitimate jobs and causing irreversible damage to ecosystems and human lives. These alarming consequences are especially evident in developing countries, holding back progress, increasing costs and pushing achievement of the goals further away. With regard to challenge of financing development, the economic leakages across the sectors susceptible to illicit trade create an annual drain on the global economy of US$2.2 trillion, [1] and present a triple threat to financing the investment needed to reach achieve the SDGs.[2] In short, illicit trade:

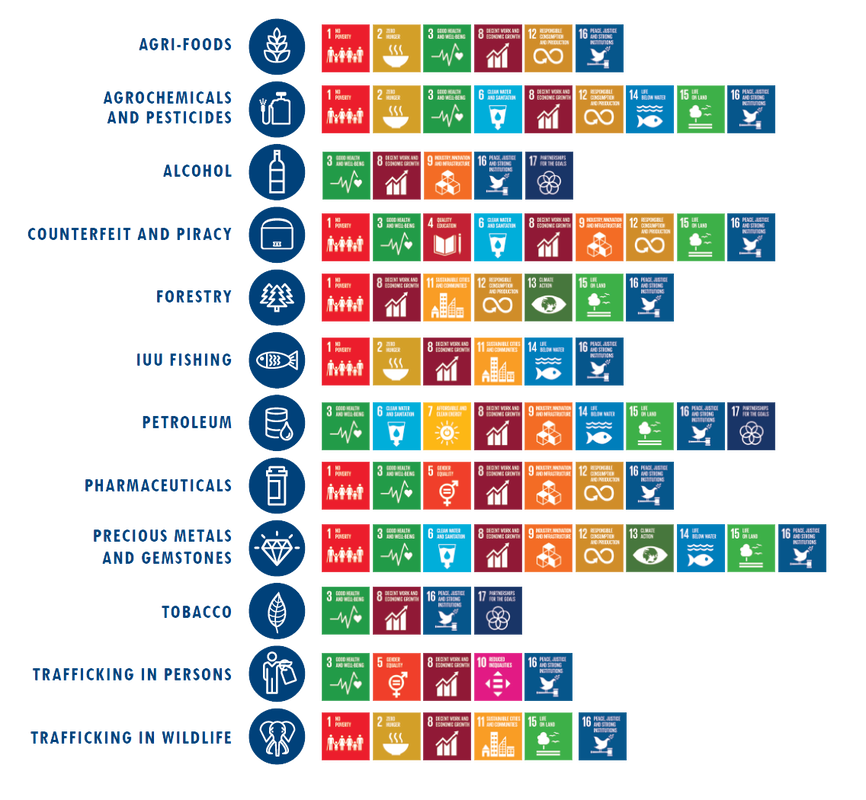

This is especially important in the light of the 2019 Financing for Sustainable Development Report, which warns that mobilizing sufficient financing remains a major challenge in implementing the 2030 Agenda and investments that are critical to achieving SDGs remain underfunded. [3] Mapping illicit trade against the SDGs The 2030 Agenda obligates member states—not the UN—to take steps to implement the SDGs and report on progress. As such, the UN itself will not be “implementing the SDGs”. Instead, the UN’s role is to help governments implement, report on progress, and share data. In order to help governments better understand how their efforts to achieve sustainable development must account for the negative forces of illicit trade, the Transnational Alliance to Combat Illicit Trade (TRACIT) prepared a study that maps the 17 UN SDGs against the following sectors: agri-foods, alcohol, fisheries, forestry, petroleum, pharmaceuticals, precious metals and gemstones, pesticides, tobacco, wildlife and all forms of counterfeiting and piracy. These sectors were chosen because they participate significantly in international trade and they are particularly vulnerable to illicit trade. Trafficking in persons is also examined as a particularly abhorrent phenomenon affecting supply chains and basic human rights as well as contributing to illicit trade practices. TRACIT collaborated with the UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) to initiate a dialogue on Illicit Trade and the Sustainable Development Goals. [4] The meeting was held at UNCTAD Headquarters in Geneva on 18 July 2019, and was designed to help governments understand the challenge of illicit trade and to consider policy measures that account for the negative impacts of illicit trade on the SDGs.

In many ways, achieving SDG 16 is prerequisite for achieving all the goals, as it aims to deliver peaceful and inclusive societies with effective governance based on rule-of-law principles. Illicit trade–in all its forms–stands in direct juxtaposition to this goal and threatens SDG 16 and its underlying targets: Feeding violence (16.1), exploiting women and children (16.2), undermining trust in institutions and the rule of law (16.3), generating enormous illicit financial flows (16.4), breeding corruption (16.5), and financing terrorism (16A).

Moreover, the links between illicit trade and organized crime are well established, from human trafficking networks and tobacco smuggling, to fuel theft by drug cartels and the involvement of the mafia and organized criminal groups in the trade of counterfeit goods. Communities and economies are further destabilized when billions of dollars of criminal profits are reinvested into other illicit activities. Perhaps most frightening are links to terrorist financing that heighten threats to national and global security. In addition to holding back progress, increasing costs and pushing the attainment of the goals further away, all types of illicit trade threaten inclusive economic growth and significantly hinder achievement of SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth). Lost taxes of all kinds—corporate, sales, personal income, excise and value-added—rob governments of revenues intended for schools, infrastructure and other public services. Illegal and unfair competition reduces sales and dampens the ability of legitimate companies to create lasting and dignified job opportunities. The specter of criminality and associated instabilities erodes the rule-of-law that underpins investment and weakens a country’s credit ratings, which are needed to secure financing and attract investment. Implications for G7 The sweeping, negative impacts of illicit trade on the SDGs point to a wide range of challenges for both governments and business. To remain on track towards the SDGs, countries must prioritize efforts to combat illicit trade and plug the fiscal leakages associated with it. The Group of Seven (G7) countries represent seven of the largest and most industrialized economies in the world and collectively hold roughly 58% of the world’s wealth. Given the G7’s recurring commitment to the 2030 Agenda, it is incumbent on the group to amplify its attention to the problem and to press for implementation and enforcement of all its standing declarations against illicit trade. As global leaders in trade and development, their commitment to address the threat of illicit trade on the SDGs would raise awareness and drive action on a global scale. Notably, illicit trade is not a problem confined to any single country or region; every country suffers from this menace, all that varies is the magnitude of the problem. The negative impacts also extend well beyond national borders, with extensive ripple effects across global markets. Hence, it will be expedient for G7 countries to attend and support the capabilities of other countries to better defend against illicit trade, especially developing countries who are already hard-pressed to monetize resources, commercialize innovation, attract investment, establish lasting job opportunities and create genuine, long-term economic growth. Without concurrent efforts to combat all forms of illicit trade – and the associated corruption and organized crime – the global community will not be able to achieve the overarching sustainable development goals to end poverty, protect the planet, and ensure that all people enjoy peace and prosperity. Biarritz G7 Summit The Biarritz G7 Summit has identified fighting inequality as one of its key objectives. We believe that the Summit presents a timely opportunity for Leaders to elevate priority attention to illicit trade, given its correlation to higher poverty, reduced peace and security, and income, health and gender inequality. The SDGs are integrated and indivisible in nature with significant inter-linkages across the goals and targets. Ending poverty, for example, must go hand-in-hand with strategies that build economic growth and address a range of social needs including education, health, social protection, job opportunities and environmental stewardship. By the same token, a holistic approach is needed to address the significant number of interdependencies and overlapping problems relating to multiple forms of illicit trade. The impacts of illicit trade cannot be examined effectively in isolation of other sectors, nor can they be addressed in isolation of the SDGs. Fighting illicit trade must therefore be seen not only as a global responsibility of G7 leaders, but also recognized as a prerequisite to achieve the UN SDGs. Role of private sector Public and private actors can play an important role in determining a responsive, evidence-based work program for addressing illicit trade, including delineation of best practices, and, where applicable, development of regulatory standards. In this regard, the Transnational Alliance to Combat Illicit Trade (TRACIT) provides a platform for business and governments to collaborate holistically to mitigate the incumbrance of illicit trade on the SDGs. Mapping the impacts of illicit trade on the UN Sustainable Development Goals is part of TRACIT’s contribution to the partnership approach embodied in SDG 17 and a means by which business, the public sector and civil society—working in partnership—can more effectively achieve the goals. Louis Bonnier Director of Programs, TRACIT Notes [1] Global Financial Integrity. (2017). Transnational Crime and the Developing World. Washington D.C.: Global Financial Integrity [2] Australian Government Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. (n.d.). Financing the Sustainable Development Goals. Canberra: DFAT. [3] Inter-agency Task Force on Financing for Development, Financing for Sustainable Development Report 2019, https://developmentfinance.un.org/node/2463 [4] https://unctad.org/en/Pages/MeetingDetails.aspx?meetingid=2182 This Op-ED was originally published by World Economic Forum (WEF)

The trade in counterfeit goods endangers consumers and diminishes public health. According to the World Health Organization, substandard and fake antimalarial medicines alone cause more than 100,000 deaths per year in Sub-Saharan Africa. Pneumonia that goes untreated owing to fake, substandard or otherwise ineffective illicit medicines may take the lives of 150,000 children worldwide every year – roughly equivalent to the total number of deaths in airplane crashes from the 1920s until today, but garnering far fewer headlines. Illicit trade pushes endangered species to the brink of extinction and causes irreversible damage to ecosystems For instance, illegal logging, with an estimated annual value of up to $157 billion, is the world’s most profitable crime involving natural resources. It can account for more than half of all forestry activities in important tropical forests, such as the Amazon Basin, Central Africa and Southeast Asia, making it a primary malefactor in the fight against climate change. Illicit trade is a serious threat to the rule of law Links between illicit trade and organized crime are well established, from human trafficking networks and tobacco smuggling, to fuel theft by drug cartels and the involvement of the mafia and organized criminal groups in the trade of counterfeit goods. These malignancies weaken law enforcement and destabilize communities and economies. Perhaps most frightening are the links to terrorist financing that heighten threats to national and global security. Indeed, illicit trade is not a problem confined to developing countries. Every country suffers from this menace, all that varies is the magnitude of the problem. The blight of illicit trade is widely acknowledged by global governance bodies. Currently, no fewer than 20 intergovernmental organizations tackle this issue, largely by sector or subject. Our concerns about illicit trade are common, but our efforts are scattered While each form of illicit trade has its own characteristics and drivers, we often see the same criminal groups using the same routes, the same means of transport and the same concealment methods behind multiple forms of illicit trade. A segmented approach to tackling illicit trade also precludes our ability to consider the interconnected nature of the problem and to appreciate commonalities and points of convergence across sectors. The result is a disjointed international response, with little cross-cutting work done either in the form of shared resources or shared recommendations addressed to national governments. This undermines a more effective governmental response to the problem. As well as governments and international organizations, the private sector needs to play a pivotal role too. Not only is the private sector severely affected by illicit trade, but it is part of the solution through the technologies it develops and the measures it can take to protect and secure supply chains. The need for a new, cross-sector approach to address illicit trade is evident. It is vital to link existing initiatives. A global forum is needed to act as a connecting hub, to explore multidisciplinary dimensions. We recognize the problem and we must act. Our dialogue on illicit trade is an attempt to start the conversations that will move us towards the creation of a common front. We must globally address the commonality of illicit trade mechanisms to defend the mission to achieve the SDGs. Only then can we safeguard people and their livelihoods from this worldwide scourge. Pamela Coke-Hamilton Director Division on International Trade and Commodities, United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) Jeffrey Hardy Director-General Transnational Alliance to Combat Illicit Trade (TRACIT) This post was originally published by Inter Press Service (IPS)  Since the 2011 revolution, Tunisia has been heralded as a model of democratic transition. However, nine governments in the past seven years have been struggling to revive the economy and the North African state faces the difficult task of maintaining faith in democracy amid a lagging economy, rising security challenges, and widespread corruption. This challenge is exacerbated by a historic dependence on informal cross-border trade coupled with an economy that is itself largely informal, accounting for as much as 50% of Tunisia’s GDP. Taken together, these factors have provided fertile grounds for illicit trade to flourish. Although headlines commonly focus on the illegal imports of fuel and tobacco, a wide variety of other products such as pharmaceuticals, fruit and vegetables, electronics, home appliances, clothes, and shoes are smuggled in and out of the country. And, if these goods and the transactions remain within the informal network, the loss of government revenues can be significant. Illicit trade also undermines legitimate business, who can’t compete against smugglers. Furthermore, it deters foreign investments in the struggling economy. Given its linkages to organized criminal activity, illicit trade can underpin wider risks to national and regional security. This is especially the case when existing routes and markets for cross-border smuggling of consumer products are exploited by criminal groups, including non-state armed actors, for trafficking in high profile illegal goods, such as drugs and arms. To help inform governments on the effectiveness of their efforts to fight illicit trade, the Transnational Alliance to Combat Illicit Trade (TRACIT) commissioned the Economist Intelligence Unit to produce the Global Illicit Trade Environment Index as a tool to measure the extent to which countries enable or inhibit illicit trade. Recent findings from the Index underscore the continued challenge that Tunisia faces in combatting illicit trade despite laudable efforts undertaken in recent years, including the Government’s crackdown on corruption and organized crime in 2017 that led to the arrest of several mafia bosses and smuggling ringleaders. Tunisia ranks 53rd out of 84 countries evaluated worldwide. The overall low score is primarily a result of major price and tax differentials with its neighboring countries, systemic corruption, a lack of legal job opportunities in the formal market and porous borders, which together create an environment where illicit trade thrives. Tunisia is by no means alone in facing this threat. All countries in the region are challenged to protect their economies from illicit trade. Algeria is ranked 58, Morocco is 65 and Libya holds the lowest ranking on the Index at 84. Clearly, more needs be done stop the surge in illicit trade that is flooding North Africa and drowning out economic development opportunities. Yet, finding solutions is not a simple task. Smuggling economies have been an integral component of regional trade for centuries, with contraband and informal commerce serving as the main sources of employment in some border communities. The evolving geopolitics in the wake of the Arab Spring have changed security dynamics in the region, opening new routes and markets for exploitation of a broad range of illicit goods. The Transnational Alliance to Combat Illicit Trade (www.TRACIT.org) is stepping up to the challenge by leading business engagement with national governments and intergovernmental organizations to develop a comprehensive and effective anti-illicit trade program to curb illicit goods that harm legitimate businesses, workers, consumers and governments. During a special event in Tunis hosted by American Chamber of Commerce Tunisia (AmCham Tunisia), TRACIT highlighted a number of priority areas that Tunisia might consider to enhance its overall policy environment to discourage illicit trade. This includes a national strategy that addresses incentives for smuggling, such as reforming administered prices and subsidies, tariff policies and technical constraints to legal importation. While important pieces of legislation have been enacted in recent years, which led, among others, to a strengthened legal framework against intellectual property infringements and a better protection of whistle blowers in corruption cases, the enforcement of existing laws needs to be improved. To do so, it will be paramount to ensure the allocation of proper human and financial resources. Crucially, policies to address illicit trade will need to be holistic and factor in broad social impact and local development issues. This includes steps to ensure that policies do not inadvertently de-stabilize communities that currently depend on informal cross-border trade. It is important that efforts to disrupt illicit trade include a development aspect to provide border regions with sustainable alternative sources of livelihood. Finally, tackling illicit trade will also require improved and deepened cooperation between neighboring countries. Disparities in different governments’ policies and subsidies create large differences in prices and taxes and arbitrage opportunities for traffickers in illicit goods. As far as possible, Tunisia should seek to align tariff rates and subsidy policies with its neighbors, strengthen border control and integrate the illicit trade threat into bilateral and regional-level discussions. Tunisia, and the region more broadly, will continue to struggle with illicit trade until the root causes are targeted and abated. TRACIT looks forward to collaborating with the Tunisian government and private sector stakeholders to advance the anti-illicit trade agenda and ensure clean and safe trade and sustainable economic development. Stefano Betti Deputy Director-General, TRACIT Email: [email protected] Twitter:@TRACIT_org

Last week I had the privilege of leading a delegation of member companies of the Transnational Alliance to Combat Illicit Trade (TRACIT) to meet with government officials and business leaders in Bogota, Colombia. Our message was straightforward: To effectively curb illicit trade, Colombia must step up its regulatory enforcement efforts, develop a comprehensive anti-illicit trade program and work more closely with the private sectors that are vulnerable to illicit trade. To demonstrate our commitment to the process, we carried a list of policy recommendations designed just for Colombia and supported by data from an Economist Intelligence Unit’s (EIU) Global Illicit Trade Environment Index, which TRACIT had commissioned to rank 84 countries (95% of global GDP and trade) on the extent to which they enable of prevent illicit trade.

Colombia ranks 43 out of 84 countries on the Index, primarily because of issues around transparency and governance of its Free Trade Zones (FTZs). TRACIT also commissioned the EIU to produce a 5-Free Trade Zone Case Study report to provide more context for what is happening in FTZs, and focused on several Latin America FTZs, including the FTZ of Colon in Panama, the Corozel Free Zone in Belize and the Maicao Special Customs Zone in Colombia. We discussed with Colombian government leaders our mutual concern that illicit trade is rampant in the region thriving on limited governance of the three major Zones. Deceptive transshipment practices, mislabeling and fraudulent invoices allow illegal traders to bypass sanctions, trade tariffs and regulations by hiding the identity of the country of origin or the illicit nature of the goods, as well as the final destination countries. Criminal operators exploit unregulated zones to manufacture or assemble products from raw materials or subcomponents, and then package or repackage the final illicit products for further shipment. The good news is that we left Bogota with the distinct impression that the new Colombian government is suitably aware of the problem, has the political will to implement a comprehensive program to curb it and is willing to work with the private sector and consider our recommendations. Brig. General Juan Carlos Buitrago, Director of Fiscal Police and Customs of Colombia, for example, explained in great detail how the Administration is working across its internal departments and states, and with neighbors in Latin America and key regional and multilateral organizations to implement its laws, step up enforcement against corruption and curb the flow of illicit trade through its ports, airports and cross-ways through its borders. This is good news for a country that has been beleaguered by all sorts of illicit trade for decades. It’s a clear sign that change is afoot, and I can say that TRACIT and our member companies are committed to working with Colombia to fight illicit trade and to make Colombia a model for clean trade zones, which will be good for Colombia’s economic growth and consumer safety. Cindy Braddon Head of Communications and Public Policy, TRACIT Email: [email protected]/ Twitter:@TRACIT_org This post was originally published by Myanmar Times

Since initiating reform in 2011, Myanmar has made progress in rejoining regional and international communities – transitioning to a market economy, liberalising trade and investment and promoting industrial development. Yet decades of political instabilities and civil unrest have sown the seeds of an extensive illegal economy, ranging from illicit trade in drugs, logging and mining to counterfeiting and wildlife and human trafficking. Some of the problem can be attributed to Myanmar’s location in the middle of the East-West trade routes and its long and porous borders with China, India, Bangladesh, Thailand and Laos. These borders are difficult to police comprehensively, which allows smugglers to move illegal products in large volumes. The situation has been exacerbated by poor governance structures, archaic laws and pervasive corruption, all of which have combined to give rise to a black-market economy where illicit trade flourishes. The scope and depth of this varied illegal activity presents significant challenges for the country’s continued economic development and regional integration; it also poses significant risks to Myanmar’s environmental integrity (e.g. illegal logging) and the health and safety of its consumers (e.g. illicit trade in alcohol). To help inform governments on the effectiveness of their efforts to fight illicit trade, the Transnational Alliance to Combat Illicit Trade (TRACIT) commissioned the Economist Intelligence Unit to produce the Global Illicit Trade Environment Index as a tool to measure the extent to which countries enable or inhibit illicit trade. Recent findings from the Index underscore the challenge that Myanmar faces in combating illicit trade. Myanmar ranks 82nd out of 84 countries evaluated, with an overall score of 23.0 (out of 100). This means that — apart from Iraq and Libya — Myanmar shows the poorest structural capability to effectively address illicit trade. Regionally, Myanmar is well behind its neighbours in both ASEAN (Singapore, 24th, Malaysia, 47th and Thailand, 48th) and APEC (e.g. Australia, 5th, Hong Kong, 12th). In producing the Index, we found the overall policy environment in Myanmar is held back by fragile institutions and governance, which together enable the supply of illicit goods to both enter the country and transit through it onto other destinations. Low level of penalties, and weak coordination, monitoring and enforcement mechanisms on corruption, meanwhile, hinder the implementation of many anti-illicit trade policies. Clearly, more needs to be done in the coming years so that the environment for illicit trade becomes less hospitable for traffickers and traders. And, we hope that this week’s Anti-Illicit Trade Forum in Nay Pyi Taw, organised by the European Chamber of Commerce in Myanmar (EuroCham), will raise awareness of the issues surrounding illicit trade in this country. As a partner to the Forum, TRACIT will present findings from the Index, with the objective to help policymakers better understand the regulatory environment and economic circumstances which enable illicit trade. We also hope that the Forum can accelerate the process of identifying policy gaps and implementing tangible actions that government and industry can take now to improve Myanmar’s ability to defend against illicit trade. There are a number of steps that Myanmar can take to improve its overall policy environment to discourage illicit trade. At the national level, for example, there needs to be improved inter-agency cooperation, particularly law enforcement agencies such as the ministries of finance, commerce, border affairs, the police force and General Administration Department under the home affairs ministry. Limited or ineffective coordination between government agencies is often exploited by illicit traders. In addition, Nay Pyi Taw could initiate partnerships to leverage the strengths of the private sector, which can be a critical partner for governments in the fight against illicit trade. EuroCham and the companies that form its Anti-Illicit Trade Advocacy Group have taken a proactive stance on the issue and can serve as valuable partners for intensifying working relationships between business and government. Finally, addressing corruption in customs and law enforcement must be tackled head on if strategies to combat illicit trade are to have any chance for success. The transnational nature of illicit trade requires that countries look beyond their own borders. As such, Myanmar must reach out to its neighbours and call for greater government-to-government cooperation, especially in the areas of customs, law enforcement and information exchange on exports and high-risk products vulnerable to smuggling. Addressing vulnerabilities and security challenges created by illicit trade will also be critical as Myanmar moves towards deeper economic integration with its trading partners via various trade agreements, and as it participates more intensely in regional economic cooperation with the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC). The challenges facing policymakers in addressing multiple vulnerabilities in the economy remain significant. For any sustained success, it will be crucial that all parties live up to their formal engagements and set up the envisaged institutional, regulatory and legislative measures without delay. Myanmar is by no means alone in facing this challenge. EuroCham and TRACIT look forward to collaborating with the government here and private sector stakeholders to advance the anti-illicit trade agenda and ensure clean and safe trade and sustainable economic development. Jeffrey Hardy Director-General, TRACIT Filip Lauwerysen Executive Director, European Chamber of Commerce in Myanmar

With the UK signing on to the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) Protocol to Eliminate Illicit Trade (the Protocol), last week, the Protocol finally achieved the threshold support needed for it to enter into force.[i]

This is a significant milestone in the fight against illicit trade in tobacco, specifically; and it’s a strong signal that the international governance community has an appetite to rally its forces against illicit trade generally. Tobacco is perhaps the most widespread and well-documented sector vulnerable to illicit trade[ii] and the WHO reports that one in every 10 cigarettes consumed globally is illicit.[iii] Like virtually all forms of illicit trade, this illegal activity robs governments of tax revenue, fuels corruption and terrorism, and expands the global illegal economy, which hampers competition and free trade and subsidizes other forms of criminality, including drugs, arms and human trafficking.[iv] For legal businesses operating in the tobacco sector, damages include trademark infringement, lost market share and increased supply chain costs associated with monitoring infrastructure and implementing trace and trace technologies. For the consumer, it means exposure to unregulated and adulterated products. The Protocol contains several measures that should prove effective for improving security in the legal supply chain, including the establishment of a global tracking and tracing system and stricter penalties for offences, liability and seizure payments. Moreover, it includes several measures aimed at promoting international cooperation, including on information sharing, technical and law enforcement, cooperation, mutual legal and administrative assistance, and extradition. While the entry into force of the Protocol is an important step in itself, this really is just the starting point. For the Protocol to effectively address the problem, many more countries will need to become parties to it. And, it will be crucial for those parties to live up to their formal engagements and set up the envisaged institutional, regulatory and legislative measures without delay. Beyond tobacco, TRACIT believes that the Protocol holds enormous potential to support and leverage efforts to combat other forms of illicit trade that similarly exploit regulatory controls supply chain vulnerabilities. For example, the requirement to “implement effective controls on all manufacturing of and transactions in, tobacco products in free zones” will ramp up attention to suspect manufacturing processes in the zones. Similarly, national measures adopted under Article 18—calling on Parties to allow for the use of special investigative techniques—can be applied to a broad range of illicitly traded goods across sectors. Other tools can be applied to fight illicit trade more broadly, such as requirements to establish a licensing system for supply chain actors and shaping effective customer due diligence processes. These measures can all serve as benchmarks for policy-makers intent on tackling illicit trade in other sectors. The First session of the Meeting of the Parties to the Protocol will take place in Geneva, Switzerland, from 8-10 October 2018. Meetings of the Parties are expected to be convened at regular intervals of time in order to review and promote the implementation of the Protocol. The October meeting will be a particularly interesting event as the first testing ground of the willingness of its Parties to turn words into deeds. Notes [i] World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. (2018, June 28). The Protocol to Eliminate Illicit Trade in Tobacco Products is live! [Press release]. Retrieved from: http://www.who.int/fctc/mediacentre/press-release/protocol-entering-into-force/en/ [ii] Melzer, S. and C. Martin (2016). "A brief overview of illicit trade in tobacco products", in Illicit Trade: Converging Criminal Networks, OECD Publishing, Paris. Retrieved from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264251847-8-en [iii] World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. (2018, June 28). The Protocol to Eliminate Illicit Trade in Tobacco Products is live! [Press release]. Retrieved from: http://www.who.int/fctc/mediacentre/press-release/protocol-entering-into-force/en/ [iv] US State Department. (2015, December). The Global Illicit Trade in Tobacco: A Threat to National Security. Retrieved from: https://2009-2017.state.gov/documents/organization/250513.pdf

Illicit trade has a particularly debilitating effect on legitimate business, in terms of lost market share, slower growth, damage to business infrastructure, reputational harm and rising supply chain compliance, security and insurance costs. For governments, illicit trade has an extensive destabilizing impact on global security due to its central role in facilitating transnational organized crime and illegal flows of money, people and products across borders. This in turn undermines the rule of law, giving rise to a hostile business environment that discourages investment.

In addition to distorting markets and draining public revenues, illicit trade undermines society’s efforts to achieve the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) with negative impacts on consumers, workers and the environment.

The world needs sustained G7 stewardship Representing the world's seven most industrialized economies, the G7 has shown leadership in curbing several illicit trade issues. At the 2006 St. Petersburg Summit, Leaders agreed to strengthen individual and collective efforts to combat piracy and counterfeiting,[3] and six years later at Camp David they underscored the role that high standards for Intellectual Property Protection (IPR) and enforcement have in combatting illicit trade in pharmaceuticals.[4] At their 2013 Lough Erne Summit, Leaders affirmed commitments against the illicit trade in endangered wildlife species, corruption, transnational organized crime and human trafficking.[5] They also expressed their commitment to support responsible, conflict-free sourcing of minerals and precious stones. The 2015 Lübeck Foreign Ministers' Statement on Maritime Security,[6] and the subsequent 2016 Hiroshima Statement,[7] also saw the G7 pledge to step up efforts to prevent illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing. And at the 2016 Ise-Shima Summit, Leaders pledged to tackle illegal logging.[8] These initial steps and commitments address significant areas of illicit trade and admirably demonstrate the clout of G7 Leaders to address major, cross-border socio-economic challenges. Nonetheless, there is a pressing need for sustained G7 leadership to address the persistent and multiplying threat of illicit trade to economic growth and prosperity. While globalization has brought with it many benefits, the massive volumes of international trade and the proliferation of supply chain nodes have increased complexities and vulnerabilities to the benefit of transnational organized crime. Here are some astonishing facts:

Given the G7’s recurring commitment to the 2030 Agenda, these threats compel the G7 to amplify its attention to the problem and to press for implementation and enforcement of all its standing declarations against illicit trade. Without concurrent efforts to combat all forms of illicit trade – and the associated corruption and organized crime – the global community will not be able to achieve the overarching sustainable development goals to end poverty, protect the planet, and ensure that all people enjoy peace and prosperity. Fighting illicit trade must therefore be seen not only as a global responsibility of G7 leaders, but also recognized as a prerequisite to achieve the UN SDGs.

Spotlight on improving integrity in Customs and free trade zones Breaches of integrity in global supply chains, especially in border control, present significant non-tariff barriers to trade that hamper economic growth and trade performance. Recent figures from the OECD show that improving integrity policies in customs alone has the potential to reduce trade costs by 0.5% and 1.1%.[20] Breaches in integrity in customs also contribute strongly to facilitating illicit trade: Customs officers are on the front-line conducting inspections and detecting and seizing illicit goods. If this role is compromised, the system fails and enables opportunities for illegal trade, criminal activity, illegal financial flows and trafficking in products and persons. Promoting integrity in customs can therefore generate dual benefits of reducing trade costs and mitigating flows of illicit trade, delivering significant benefits to the world trade system and economic development at large. The misuse of transshipment points in cargo routings, especially through Free Trade Zones (FTZ), represents another challenge. Deceptive transshipment practices, mislabeling and fraudulent invoices allow illegal traders to bypass sanctions, trade tariffs and regulations by obfuscating the identity of the country of origin or the illicit nature of the goods. Unrestricted regimes for transshipment and transit of goods through FTZs contribute to a wide range of illicit activities, including money laundering, organized criminal activity in illegal wildlife trade, tobacco smuggling, fraud, and counterfeiting and piracy of products. OECD research shows that an additional FTZ within an economy is associated with a 5.9% increase in the value of exported counterfeit and pirated goods on average. Enhancing transparency in FTZs is an important measure to reduce trafficking vulnerabilities and strengthen the integrity of global supply chains. The Charlevoix Summit represents an opportunity for G7 Leaders to collectively underscore the importance of clean international trade by driving the process towards better integrity in customs and improved transparency of FTZs. A unified business response to illicit trade The transnational problem of illicit trade has clearly grown well beyond the capabilities of individual governments. What is needed is a sustained, holistic and coordinated response by governments to address the multifaceted nature of this threat. Equally important is the recognition that the private sector can be an important partner in the fight against the unfettered flow of fake and harmful goods across borders.[21] Consequently, any long-term solutions to the threat of illicit trade will depend on sustained collaboration between governments and private sector partners. Business can contribute by continuing to develop technical solutions that protect the integrity of supply chain, and share intelligence, data, resources and measures that effectively control illicit activity. And business is willing to work with partners to convene stakeholders, improve awareness, expand the knowledge base, and energize the global dialogue. Governments, however, need to improve regulatory structures, set deterrent penalties, rationalize tax policies, strengthen capacity for more effective enforcement, and educate consumers. This is a matter of urgency and G7 government efforts to fight illicit trade should be considered investments that pay tangible dividends to economic development and global security. The Transnational Alliance to Combat Illicit Trade (www.TRACIT.org) is responding to this challenge by leading business engagement with national governments and intergovernmental organizations to ensure that private sector experience is properly integrated into rules and regulations that will govern illicit trade. TRACIT represents companies and organizations that have a shared commitment to combatting illicit trade and ensuring the integrity of supply chains. Addressing illegal trade – whether that be smuggling of alcohol, illegal logging, counterfeit pesticides or petroleum theft and trafficking in persons – presents common challenges for a growing number of industries. All stakeholders have an interest in stamping out illicit trade; and all benefit from collective action. In this regard, business offers its support to the G7 to advance implementation of its many commitments from past Summits. And, we suggest that Charlevoix presents a timely opportunity for Leaders to elevate priority attention to illicit trade and work with business to address associated threats to safety, security, cybersecurity, natural resources and economic development. Notes [1] WEF. (2015). State of the Illicit Economy. Briefing Papers, October 2015. Cologne/Geneva: World Economic Forum. Retrieved from http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_State_of_the_Illicit_Economy_2015_2.pdf [2] CNBC. (2017, July 3). The illicit economy could be as big as a G7 country: Pro. CNBC. Retrieved from https://www.cnbc.com/video/2017/07/03/the-illicit-economy-could-be-as-big-as-a-g7-country-pro.html [3] G8. (2006). Combating IPR Piracy and Counterfeiting. Retrieved from http://www.mofa.go.jp/policy/economy/summit/2006/ipr.html [4] G8. (2012). Camp David Declaration. Retrieved from https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2012/05/19/camp-david-declaration, para 9. [5] G8. (2013). Lough Erne Leaders Communique. Retrieved from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/207771/Lough_Erne_2013_G8_Leaders_Communique.pdf, para 40 [6] G7. (2015). G7 Foreign Ministers’ Declaration on Maritime Security Lübeck. Retrieved from http://www.mofa.go.jp/files/000076378.pdf, para 9. [7] G7. (2016). G7 Foreign Ministers’ Statement on Maritime Security Hiroshima. Retrieved from http://www.mofa.go.jp/files/000147444.pdf [8] G7. (2016, 27 May). Ise-Shima Leaders’ Declaration G7 Ise-Shima Summit. Retrieved from http://www.mofa.go.jp/files/000160266.pdf [9] OECD/EUIPO (2016), Trade in Counterfeit and Pirated Goods: Mapping the Economic Impact, OECD Publishing, Paris. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264252653-en. [10] TERA Consultants. (2010). Building a Digital Economy: The Importance of Saving Jobs in the EU's Creative Industries. Paris: TERA Consultants. Retrieved from https://euipo.europa.eu/ohimportal/documents/11370/71142/Building+a+Digital+Economy,+the+importance+of+saving+jobs+in+the+EUs+creative+industries [11] Frontier Economics. (2016). The Economic Impacts of Counterfeiting and Piracy. n.p.: Frontier Economics. Retrieved fromhttps://www.inta.org/communications/documents/2017_frontier_report.pdf [12] Hoare, A. (2015). Tackling Illegal Logging and the Related Trade What Progress and Where Next? London: Chatham House. Retrieved from https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/files/chathamhouse/publications/research/20150715IllegalLoggingHoareFinal.pdf; Biderman, R and Nogueron, R. (2016, December 9). Brazilian Government Announces 29 Percent Rise in Deforestation in 2016. World Resources Institute. Retrieved from http://www.wri.org/blog/2016/12/brazilian-government-announces-29-percent-rise-deforestation-2016; Plumer, B. (2015, March 2). Deforestation in Brazil is rising again — after years of decline. Vox. Retrieved from https://www.vox.com/2015/3/2/8134115/deforestation-brazil-increasing [13] Cone, A. (2017, February 5). Report: Human trafficking in U.S. rose 35.7 percent in one year. UPI. Retrieved from https://www.upi.com/Report-Human-trafficking-in-US-rose-357-percent-in-one-year/5571486328579/ [14] Kelly, A. (2017, September 19). Latest figures reveal more than 40 million people are living in slavery. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2017/sep/19/latest-figures-reveal-more-than-40-million-people-are-living-in-slavery [15]Desjardins, J. (2017, May 7). Fuel theft is a big problem. Business Insider. Retrieved from http://www.businessinsider.com/fuel-theft-is-a-big-problem-2017-5 [16]Scott, A. (2016). How Chemistry is Helping Defeat Fuel Fraud. Chemical & Engineering News, 94(5), pp. 20 – 21. [17] Euromonitor International. (2018). Illicit Trade in Tobacco Products. London: Euromonitor International. Retrieved from http://www.euromonitor.com/illicit-trade-in-tobacco-products/report [18] Michalopoulos, S. (2017, February 7). EU anti-fraud official: Tobacco smuggling is ‘major source’ of organized crime. EURACTIV.com. Retrieved from https://www.euractiv.com/section/trade-society/interview/olaf-official-tobacco-smuggling-major-source-for-organised-crime/ [19] PWC (2016). Fighting $40bn food fraud to protect food supply. Press release.Retrieved from https://press.pwc.com/News-releases/fighting--40bn-food-fraud-to-protect-food-supply/s/44fd6210-10f7-46c7-8431-e55983286e22 [20] OECD. (2017). Integrity in customs: taking stock of good practices. Paris: OECD Publishing.Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/gov/ethics/G20-integrity-in-customs-taking-stock-of-good-practices.pdf [21] OECD. (2018). Governance frameworks to counter illicit trade.Paris: OECD Publishing.Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/gov/governance-frameworks-to-counter-illicit-trade-9789264291652-en.htm This post was originally published by Inter Press Service (IPS) Illicit trade in any of its forms—alcohol, tobacco, pharmaceuticals, diamonds, timber, ivory and oil—sits at the nexus of two social-economic disorders that challenge global stability. Firstly, the global economy remains on unsteady footing, and governments are scrambling to stimulate growth, employment and investment in infrastructure and other public programs. Secondly, the upswing in criminal activity and lawlessness—in some cases punctuated by terrorist acts—has left us all questioning our security for this generation and the next. Illicit trade exacerbates both problems and presents governments with an immediate challenge to address their pervasive and significantly negative impacts on our economy and our civil society. Economic Impacts Deriving from Illicit Trade in the Petroleum Sector Every year an estimated $133 billion of fuels are illegally stolen, adulterated, or defrauded from legitimate petroleum companies.[1] Roughly 30% of Nigeria’s refined fuel products are smuggled into neighboring states [2] and pipeline fuel theft in Mexico is at record levels [3]. This illegal activity creates an enormous drain on the global economy, crowds out billions from the legitimate economy and dislocates hundreds of thousands of jobs. Equally significant are associated fiscal losses from tax evasion and subsidy abuses that deprive governments of revenues for vital public services and force higher burdens on taxpayers—especially in developing countries where petroleum industry royalties and tax payments finance development. For example, Philippines loses $750 million annually in tax revenue from fuel adulteration and smuggling.[4] The Honorable Dakila Cua, Chairman of the Philippines House Committee on Ways & Means, told me that fuel smuggling is a vicious practice that deprives his country of precious revenues for investment in infrastructure. He confirmed that the problem is deeply embedded in the Philippine economy and throughout ASEAN economies. The value of the illegal fuel trade in Southeast Asia ranges from $2 to $10 billion a year.[5] Links to transnational Organized Crime and Terrorism The links between illicit trade and organized crime are well established. The global economic value of oil and fuel theft ranks amongst the highest of transnational crimes. Research shows connections between oil theft and drug cartels in Mexico; insurgents and human traffickers in Thailand; human smugglers in Libya; terrorists in Ireland; militant groups in Nigeria; rebel movements in Mozambique, and of course, ISIS.[6] This activity significantly threatens national and regional stability, and creates significant deterrents for business investment, which thrives in stable, peaceful environments. Notably, the criminal connection is not limited to oil and fuel theft. Transnational organized crime is involved in all forms of illicit trade, from human trafficking networks and tobacco smuggling, to the involvement of the Mafia and Camorra in the trade of counterfeit goods. Moreover, profits from one illegal activity are frequently used to finance a different type of illicit trade. Illicit Trade and Environmental Degradation Illicit trade in the petroleum sector perpetuates extensive ripple effects across global markets, including undercutting sustainable development and hastening environmental degradation. The process of illegal tapping, bunkering and ship transfers, for example, carry a higher probability for oil spills and blown pipelines, potentially causing significant damage to soil fertility, clean water supplies and marine life. Consequently, fighting fuel fraud is a global responsibility, as well as a prerequisite for the achievement of the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Solutions Despite these severe negative effects, the global problem of oil and fuel theft so far has been largely unchecked and remains mostly hidden from international attention. Any long-term solution will be dependent on sustained collaboration between governments and the private sector. Business will contribute by continuing to develop technical solutions, such as fuel markers and GPS tracking. Modern fuel-marking programs allow governments to identify stolen or diverted fuel and reduce fuel losses, while delivering improved integrity in fuel supply chains, mitigating tax evasion and subsidy abuses, and plugging revenue drains. Business also can share intelligence, data, resources and measures that effectively control this illicit activity. And Business is willing to work with partners to convene stakeholders, improve awareness, expand the knowledge base, and energize the global dialogue. Governments, however, need to improve regulatory structures, set deterrent penalties, rationalize tax policies, strengthen capacity for more effective enforcement and educate consumers. This is a matter of urgency and government efforts to fight illicit trade should be considered investments that pay tangible dividends to economic development and global security. TRACIT is responding to this challenge by leading business engagement with national governments and intergovernmental organizations to ensure that private sector experience is properly integrated into rules and regulations that will govern illicit trade. Our specific engagement in the petroleum sector stems from the shared understanding that a united industry voice is required to track, report and stop fuel fraud – from extraction to production to distribution to consumers. The geographic diversity and wide-ranging methods of oil and fuel theft and fraud require a comprehensive global approach to mitigating the problem. All stakeholders have an interest in stamping out illicit trade; and all benefit from collective action. Notes [1] Desjardins, J. (2017, May 7). Fuel theft is a big problem. Business Insider. Retrieved from http://www.businessinsider.com/fuel-theft-is-a-big-problem-2017-5 [2] Ralby, I. M. (2017). Downstream Oil Theft: Global Modalities, Trends, and Remedies. Washington, DC: Atlantic Council. Retrieved from http://www.eurocontrol.ca/images/euo_content_images/euo_pdfs_in_articles/AtlanticCouncil_Report-Downstream_Oil_Theft_January_2017.pdf [3] García, K. (2018, April 5). Crece sin freno sangría a ductos de Pemex. El Economista. Retrieved from https://www.eleconomista.com.mx/empresas/Crece-sin-freno-sangria-a-ductos-de-Pemex-20180405-0016.html [4] ADB. (2015). Fuel-Marking Programs: Helping Governments Raise Revenue, Combat Smuggling, and Improve the Environment. The Governance Brief, 24. Retrieved from https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/174773/governance-brief-24-fuel-marking-programs.pdf [5] Gloystein, H and Geddie, J. (2018, January 18) Reuters. Shady triangle: Southeast Asia's illegal fuel market. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-singapore-oil-theft-southeast-asia-an/shady-triangle-southeast-asias-illegal-fuel-market-idUSKBN1F70TT [6] Ralby, I. M. (2017). Downstream Oil Theft: Global Modalities, Trends, and Remedies. Washington, DC: Atlantic Council. Retrieved from http://www.eurocontrol.ca/images/euo_content_images/euo_pdfs_in_articles/AtlanticCouncil_Report-Downstream_Oil_Theft_January_2017.pdf Transnational Alliance to Combat Illicit Trade

The Transnational Alliance to Combat Illicit Trade (TRACIT) is a private sector initiative organized as a non-governmental, not-for-profit organization under US tax code 501(c)(6). TRACIT draws from industry strengths and market experience to build habits of cooperation between business, government and the diverse group of countries that have limited capacities for regulatory enforcement. Its work program focuses on strengthening the business response to illicit trade by exchanging information and mitigation tactics in and across key industry sectors and reducing vulnerabilities in supply chains, including transportation, digital channels, free trade zones and financial networks. TRACIT’s work program covers alcohol; agri-foods; counterfeiting and piracy; fisheries; forestry; pesticides; petroleum; pharmaceuticals; precious metals and gemstones; and tobacco. trafficking in persons, and wildlife. www.TRACIT.org : [email protected] |

About tracit talking pointsTRACIT Talking Points is a channel we’ve opened to comment on current trends and critical issues. This blog showcases articles from our staff and leadership, along with feature stories from our partners in the private sector and thought-leaders from government and civil society. Our aim is to deepen the dialogue on emerging policy issues and enforcement measures that can be deployed against illicit trade.

Categories

All

Archives

February 2024

|

|

Transnational Alliance to Combat Illicit Trade (TRACIT) is an independent, non-governmental, not-for-profit organisation under US tax code 501(c)(6).

© COPYRIGHT 2024. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. |

Follow us

|