In a compelling address to a conference hosted by the Trinidad and Tobago's Manufacturer’s Association on October 26, 2023, Jeff Hardy, the Director-General of the Transnational Alliance to Combat Illicit Trade (TRACIT), recently shared insights on collaborative strategies to combat illicit trade. The focal points of his discussion are highlighted in TRACIT’s recently published case study Good Practices in Fighting Illicit Trade: The Case of Trinidad and Tobago featuring the commendable efforts of the Trinidadian government to tackle illicit trade. The Urgency of a United Front Although Trinidad and Tobago has a strong economy and a high GDP per capita, the country faces significant vulnerabilities to illicit activities. Local reports indicate that approximately 22 percent of imported alcohol and 5-10 percent of the domestic tobacco market are affected by illicit trade, resulting in substantial revenue losses—estimated at around US$4.5 million annually. These losses, in turn, hinder the government's ability to fund crucial public services in health, security, and education. The government emphasised the need for innovative, collaborative, cross-border approaches in the fight against illicit trade. “The efforts undertaken by Trade Minister Paula Gopee-Scoon to orchestrate a holistic government approach across various agencies and fostering private sector engagement have been valuable in strengthening the nation’s endeavours to combat illicit trade,” said Jeff Hardy, Director General of TRACIT. Government Initiatives to Combat Illicit Trade Responding to the challenges posed by illicit trade, the government initiated a series of measures outlined in the Road Map for Trinidad and Tobago: Transforming to a New Economy and a New Society. One notable initiative was the creation of the National Anti-Illicit Trade Task Force, comprising representatives from various government, regulatory, and law enforcement agencies. The targeted actions address a range of sectors, including cosmetics; clothes; petroleum products; tobacco; alcohol; wildlife; music; pharmaceuticals; and intellectual property rights. The measures aim to enhance the policy and legal framework; reduce the supply of illicit goods; decrease consumer demand; improve transparency; and enhance customs procedures. Randall Karim, the Permanent Secretary of the Ministry of Trade, emphasised the importance of setting up a Task Force to review current legislation, conduct a gap analysis, and create a strong legal framework. This, he said, “Sends a strong signal that illicit trade will not be tolerated in Trinidad and Tobago”. Commendable Progress, but More to Be Done The government's proactive steps to curb illicit trade in recent years are commendable, serving as a valuable example for other nations. However, TRACIT highlights that more needs to be done, proposing additional policy recommendations to further strengthen Trinidad and Tobago's fight against illicit trade. TRACIT calls for prioritised commitments to enhance cooperation with neighbouring countries; improve data access and exchange; integrate anti-illicit trade policies into national plans for Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs); strengthen intellectual property rights enforcement; promote a clean digital environment; and fortify the customs environment. “It is evident that the government of Trinidad and Tobago has taken significant steps to prevent illicit trade in recent years. These efforts are commendable and represent meaningful steps forward - in Trinidad and Tobago and as lessons for others,” said Jeff Hardy.” Nonetheless, more needs to be done and additional policy recommendations can help Trinidad and Tobago to mitigate illicit trade more effectively.” In conclusion, Trinidad and Tobago's efforts to combat illicit trade showcase a dedicated commitment to securing the nation's economic stability and protecting public interests. By sharing these experiences, the case study serves as a valuable resource for other nations grappling with similar challenges, emphasising the importance of collaboration, innovation, and sustained efforts in the global fight against illicit trade. Meilun Yu TRACIT Staff Writer This article was originally published by the Brand Protection Professional: A Practitioner’s Journal (BPP)

You and everyone you know have run across a counterfeit while shopping online. While we were trapped inside during the pandemic, we turned to ecommerce as the only source for the things we needed most from essentials (remember the illusive search for toilet paper) to items that would make us feel better about working, dining, and sleeping all day every day in the same place. The surge in online shopping brought on by the pandemic has stayed with us. Now we can buy anything, anywhere and it will arrive almost immediately, which is perfect for a society that more and more demands instant gratification. As with every good thing, however, criminals figure out ways to profit by exploiting weaknesses on online platforms and the consumers that shop there. Selling and profiting on counterfeits in an online environment – where there is lax oversight and a focus on facilitating sales without the same due diligence requirements in place for brick-and-mortar stores – has become a significant consumer protection problem that must be addressed immediately. The Transnational Alliance to Combat Illicit Trade (TRACIT), a US-based independent multinational business association, is focused on stopping counterfeit and illicit goods across ten industries by addressing all forms in which they are traded. Our experience is that brand owners are committed to protecting their intellectual property and their brands and invest significant time and resources into working with ecommerce and social media platform, employing technologies and bringing legal enforcement actions aimed at eliminating counterfeits that potentially harm with products that do not meet regulatory and safety standards. Fortunately, Congress passed the INFORM Consumers Act last year. This is a crucial, albeit small step along the path to ensure that consumers have a safe and secure online shopping experience. For the first time, online marketplaces will have to conduct some basic due diligence to better vet their third-party sellers and disclose key information about the sellers to consumers. Also, importantly, platforms must have an easy-to-use portal on each product listing for consumers to report suspicious activity. The Federal Trade Commission is enforcing the law and stiff fines are available for violations. We need to go further to incentivize online marketplaces by creating liability if they do not implement certain best practices. When a platform involved with the transaction guides, encourages, and controls every step of the interaction between buyer and a merchant; when it actively promotes, controls, consummates, and guarantees the transaction, that platform is far more than an internet venue that connects purchasers and merchants. It is now facilitating the sale of counterfeits and must take responsibility for its role. For the reason, the liability provisions of the SHOP SAFE Act of 2023 are the essential next step in responsible public policy to protect consumers. Currently ecommerce and social media platforms are telling us they are regularly removing thousands and thousands of fraudulent products listings. Now is the time for standardized and enforceable best practices across online marketplaces to insure they stop the bad actors from ever listing their counterfeit products in their stores from the get-go, and bar counterfeiters from accessing their platforms after repeatedly violating their terms. The SHOP SAFE Act of 2023 does just that. The bill makes online marketplaces more accountable for implementing key best practices. It provides a safe harbor from liability if platforms proactively screen against fakes and counterfeits; promptly remove counterfeit listings; enforce their policies; communicate with brands and law enforcement; and ban counterfeiters from hopping back on their platforms. Voluntary and inconsistent practices are not working. Let’s take the next step to better protect our consumers, our economic and national security. Let’s work together to bar repeat offenders from ever being able to sell in their marketplaces again. Let’s pass SHOP SAFE in the US and make it a global standard. Cindy Braddon Head of Communications and Public Policy, TRACIT Excerpts from Stefano Betti Address to FICCI Anti-Smuggling Day Conference on February 11, 2022.

Good morning, ladies and gentlemen, and many thanks to FICCI for the opportunity to say a few words on the occasion of the Anti-Smuggling Day. Smuggling is a complex and multifaceted phenomenon. It is a vast subject, and there are many perspectives that could be addressed. So, in the little time available to me, I will just put forward a few key points for your consideration. Those are points that TRACIT - the organization I am representing here - is busy addressing with its governmental partners, international organizations and the business community at large. The term “smuggling” is itself the object of numerous definitions that differ from each other depending on whether they are used in a legal, policy, law enforcement or academic context. There are also variations based on the type of goods under consideration. Despite the differences, however, all existing definitions have a minimum common denominator, which is captured in the idea of smuggling being a set of activities aimed at moving or facilitating the moving of goods across borders in violation of applicable laws. It is important to highlight that smuggling activities generate a wide range of negative impacts on society and the economy. Notably:

In addressing smuggling - either in general or in relation to specific manifestations - I always find it useful to examine the problem in terms of its drivers, enablers, and the possible responses to it. Let me then start with the drivers. I will mention just a few:

Turning to the enablers:

Which leads me to say something about the ways to respond to smuggling practices. Without claiming to be exhaustive, there are two or three of points worth throwing into the discussion:

Let me conclude by saying that smuggling is one of the oldest activities that humans have engaged in since they have organized themselves in sovereign political communities. It cannot be eradicated, but it can be better controlled, and its consequences mitigated. I very much hope that this important event will contribute to rejuvenating efforts in this area and steer policy-makers’ agenda towards renewed attention for this problem.  This article was originally published by the Group of Nations G7 Summit Global Briefing Report Review Illicit trade is a major and growing policy challenge worldwide. From smuggling, counterfeiting and tax evasion, to the illegal sale or possession of goods, services, and wildlife, governments are losing billions in tax revenues, legitimate businesses are undermined, and consumers are exposed to poorly made and unregulated products. These crimes in turn are tied to human rights and labor rights violations, money laundering, illicit financial and arms flow, child labor, and environmental degradation. The World Economic Forum's annual Global Risks Report lists illicit trade and the associated proliferation of illicit economic activity as a “global risk” with the potential to cause significant negative impact for several countries or industries within the next 10 years. For governments, illicit trade has an extensive destabilizing impact on global security due to its central role in facilitating transnational organized crime and illegal flows of money, people and products across borders. This in turn undermines the formal authority of rule of law, which can destabilize business and discourage investment. The Group of Seven The UK is taking on the Presidency of the G7 at a critical time for the world. While new vaccines offer a way to end the COVID-pandemic, the virus continues to wreak havoc across the globe and new variants threaten the global recovery. The pandemic has also allowed an unremitting illicit economy to expand and take root. Many factors shape the dynamics of illicit trade, from the international political and security landscape to macro socio-economic dynamics and national law enforcement capacity - all of which have been affected by the global COVID-19 pandemic. While the immediate effect was predictably to slow down all forms of economic activity, including the illicit, the COVID-19 pandemic spawned new markets for illicit trade, like falsified vaccines, and deepened age-old illicit trade in alcoholic beverages, tobacco and counterfeits. While initially set up as an informal forum for dialogue between leading economic powers to coordinate economic and financial policies, the G7 has increasingly used its clout to address common major global challenges including peace and security, counter-terrorism, development, health, climate change, as well as the threat of illicit trade. This year’s Leaders’ Summit, held in Carbis Bay, Cornwall on 11–13 June 2021, saw the G7 continue to demonstrate leadership against several illicit trade challenges: Forced Labour The G7 has made several pledges to eradicate forced labor, starting with their 2015 Elmau commitment to foster sustainable supply chains and then G7 Social Ministers pledging to promote decent work, responsible business conduct and human rights due diligence in global supply chains in 2019. This was also reinforced by G20 Labor and Employment Ministers in Mendoza, in 2018, who committed to eradicate child labor, forced labor, human trafficking, and modern slavery. Leaders in Carbis Bay continued this path by agreeing to work together to ensure that global supply chains are free from the use of forced labor - specifically highlighting state-sponsored forced labor of vulnerable groups and minorities, including in the agricultural, solar, and garment sectors - and tasked their Trade Ministers to identify areas for strengthened cooperation and collective efforts towards this goal. Human rights abuses—specifically in the form of forced and child labor—are a fundamental characteristic of illicit economic activity. Joint and decisive action by the G7 to address forced labor in global supply chains is important, but the far greater challenge that, to date, has received too little attention is addressing these human rights and labor violations in the informal sectors of the economy – many of which are tied to illicit trade. In 2019 the UN General Assembly announced that 2021 would be the “International Year for the Elimination of Child Labour”. While the past decade has seen child labour decrease by 38%, 152 million children are still affected. And the COVID-19 pandemic has considerably worsened the situation. Without decisive and coordinated action against illicit trade, governments around the world will fall short of their targets to root out child labor.  Illegal Timber Building on the 2016 Ise-Shima Summit’s pledge to tackle illegal logging, Leaders in Carbis Bay committed to ensuring that their forestry policies encourage sustainable production, the protection, conservation, and regeneration of ecosystems, and the sequestration of carbon. The inclusion of this pledge is particularly important given that reduced forest monitoring and fewer patrols by enforcement agencies during the COVID-19 pandemic has created opportunities for criminal groups to expand illegal logging activities. As a result, there has been an uptick in illegal logging, with reports of increased logging activity from Brazil, Colombia, Cambodia, Indonesia, Nepal and Madagascar. IUU fishing Illicit fishing is an abhorrent crime against planet earth and SDG 14 mandate to protect life below water. It generates billons in revenue for transnational organized crime and the criminals involved in illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing operations also make use of fishing vessels for related criminal activities, such as drugs and firearms trafficking, money laundering, tax fraud, bribery, migrant smuggling, trafficking in persons for the purpose of forced labor, piracy and acts of terrorism. Subsidies to the fisheries sector, roughly US$35 billion annually, can exacerbate unsustainable fishing practices by artificially increasing fishing capacity – which in turn promotes overfishing and other destructive fishing practices. By some estimates these subsidies have helped produce a worldwide fishing fleet that is up to 250 percent larger than is economically and environmentally sustainable, driving overexploitation of already depleted resources. This year Leaders will have a unique opportunity to make good on their longstanding pledge to step up efforts to prevent IUU fishing. If their Carbis Bay pledge of working with other WTO members in “reaching a meaningful conclusion to the multilateral negotiations on fisheries subsidies” translates into an agreement ahead of MC12, this would demonstrate the value of collective G7 action and create a pivotal moment for the world’s oceans and the livelihoods of fishers and other workers.  Online fraud The COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated the digital transformation, bringing about a surge in online shopping and other ecommerce activities. Unfortunately, this exponential growth has also brought with it a flood of online fraud, with unscrupulous counterfeiters seeking to exploit the health crisis by selling everything from fake testing kits, treatments and personal protective equipment (PPE), to falsified medicines and dubious vaccines. This development has intensified the need for better rules and standards to ensure that the business practices of ecommerce platforms sufficiently prevent bad actors from selling unregulated, unsafe or otherwise fraudulent products to consumers. The G7 has supported the WTO’s Joint Statement Initiative on E-commerce (JSI), which may provide the first steps in this direction, as the outcome of the JSI negotiations will likely affect the governance of various dimensions of e-commerce, with implications for all countries, whether they are party to these negotiations or not. The time left between now and the 12th WTO Ministerial Conference is very critical if Leaders are to address, and mitigate, the negative impact that online fraud and illicit activities have on building trust in e-commerce and ensuring consumer protection. The recovery As G7 Leaders move from crisis management into recovery mode, it will be important to amplify their attention to the problem of illicit trade and to press for implementation and enforcement of all its standing commitments. Without continued political will to prioritize the problem there is a real threat that illicit trade activities caused by the pandemic become permanent features of the post-pandemic economy. While COVID-19 has been a catalyst for new and increased illicit trade, it also underscores the importance of sustained collaboration between governments and private sector partners. TRACIT has worked with industry partners during the pandemic to publish papers and reports thar raise awareness and help protect consumers from COVID-19-related fraud. Our efforts show that business can contribute by continuing to develop technical solutions that protect the integrity of supply chain, and share intelligence, data, resources and measures that can mitigate illicit activity. And business is willing to work with partners to convene stakeholders, improve awareness, expand the knowledge base, and energize the global dialogue. Governments, however, need to improve regulatory structures, set deterrent penalties, rationalize tax policies, strengthen capacity for more effective enforcement, and educate consumers. This is a matter of urgency and G7 government efforts to fight illicit trade should be considered to be critical investments that pay tangible dividends for a strong and sustained economic recovery. Louis Bonnier Director of Programs, TRACIT

The new report shows that containerships carry more than half of all seized counterfeits and provides an urgent and compelling need for governments to set new standards for mitigating the abuse of international maritime shipping lines by illicit traders.

The Task Force meeting also addressed high-risk areas of the economy—pharmaceuticals, alcohol, food, tobacco and counterfeiting online—that were particularly impacted by illicit trade during the pandemic, and the need to evaluate best practices to improve regulations and mitigate the problem. Moving forward, TRACIT believes the Task Force should build upon the impressive body of quantitative work to more effectively deliver on its High Level Risk Forum mandate to ‘design and promote good practices in public policies as a means to reduce and deter trafficking and smuggling activities,’ and to map policies and practices and develop metrices on the governance gaps that foster illicit trade. This includes cultivating the work of the task force within OECD member governments – to ensure that work is directed to the right national agencies and that messages and guidance properly percolate throughout national capitals. For example, the OECD Council’s Recommendation on Countering Illicit Trade: Enhancing Transparency in Free Trade Zones contains much-needed guidance for OECD member states. Success here will depend on work engagement, adoption and implementation by OECD governments. The OECD has changed the game here, now it’s time from member state to see it through. The Task Force should also look at ways to increase engagement and share its experience with non-OECD Member States that value the expertise of the OECD and look to it for leadership and guidance. This includes regions such as ASEAN, which is in the process of addressing illicit trade and establishing its own policy standards. Finally, I was pleased by the continued engagement with the private sector - especially those legitimate industry players most impacted by illicit trade. Industry partners represented by the Anti Illicit Trade Expert Group of the Business at OECD share the common goal of countering illicit trade and provide critical market knowledge, supply chain expertise and technical innovation. The ongoing public-private sector dialogue ensures a more effective approach to countering illicit trade by balancing incentive setting, taking into account industry-specific sensitivities and competitive advantages on private and public sides. If there is one thing we have learned from the Task Force’s work and accomplishments over the last nine years is that mitigating the cross-sectoral challenge of illicit trade is going to require an international, coordinated, response by all affected parties – and a lot of hard work! Jeffrey Hardy Director-General, TRACIT A call to action on World Consumer Rights Day, 15 March 2021 Back in 1985, the UN Guidelines on Consumer Protection introduced a new and somewhat revolutionary set of global standards for protecting consumers from potentially hazardous goods or services.

30 years later, monumental changes in the global marketplace called for a much-needed update of the Guidelines. Among new provisions introduced in 2015, the Guidelines flagged the emerging risk of fraud to consumers shopping online, including the availability of counterfeits. But there is still much work to be done because online sales have grown to represent upwards of 15 percent of global retail sales and the value of counterfeits purchased online is over $300 Billion. Consequently, #WorldConsumerRightsDay is an appropriate day to raise awareness! Consumers are entitled to an online shopping experience that is safe and secure from fraud. Online platforms connecting people and those that profit from commerce over their websites should be responsible, comply with the law and recognize the ethical responsibility to assure consumers a safe and trusted environment. TRACIT has been pleased to work with @UNCTAD Intergovernmental Group of Experts (IGE) on Consumer Protection Law and Policy and @OECD Committee on Consumer Policy to safeguard consumers new online risks. Let’s start today, let’s work towards:

To learn more about TRACIT’s eCommerce and fraudulent advertising principles & positions, please visit: https://www.tracit.org/counterfeiting--piracy.html This article was originally published by the International Institute for Strategic Studies

As the pain of vaccine shortages is being felt across Europe, Stefano Betti warns that black marketeers may be exploiting a bigger-than-expected gap between the legal supply and demand of COVID-19 vaccines. While the approval of new vaccines against COVID-19 during the last months of 2020 was celebrated around the world, law-enforcement agencies braced themselves for the emergence of a corresponding black market in such vaccines. In early December 2020, Interpol issued an alert warning its 194 member countries to expect organised crime groups to become engaged in the falsification, theft and illegal advertising of these products. Mexican gangs have reportedly already set up manufacturing laboratories for fake vaccines. Long before the onset of the pandemic, an illicit economy for medicines had prospered globally, with a wide range of illegal products traded on the black market. Some are genuine, but may be unregistered or unlicensed. These are often ineffective – for example, because they have been smuggled without respecting storage requirements. Counterfeit medicines are the most dangerous and potentially life-threatening, especially when they contain the wrong active ingredient or the wrong amount thereof. Although we do not (yet) have data about the health risks posed by counterfeit vaccines, there is no reason to suppose that these will be less harmful than falsified medical products in general. But the consequences of the development of a black market for vaccines are potentially more far-reaching. Public-health and social consequences Despite warnings that vaccinated people might continue to spread the virus, many of those who have been inoculated may entertain a false sense of security and feel more inclined to disregard social distancing and other protective measures against the pandemic. If they have been inoculated with an illegal (and ineffective) vaccine, the risk of spreading the virus will be even greater. Moreover, when fake vaccines are supplied by criminal organisations that have actively supported impoverished communities during the pandemic, like the Mexican case mentioned above, people may be even more inclined to accept the vaccines as effective, as they come from a source that they consider trustworthy. The severity of the public-health impact generated by the above will clearly depend on the extent to which the illegal trade in vaccines will expand in the near future. Its size will, in turn, depend on the ability of governments to roll out speedy and comprehensive inoculation campaigns. In the European Union, there are indications that this objective will not be achieved any time soon. As three major pharmaceutical companies recently announced severe production shortfalls, black marketeers may be exploiting a bigger-than-expected gap between legal supply and demand. The appeal of the illegal market may be particularly strong in developing countries. According to a recent study by the Economist Intelligence Unit, ‘in poorer economies, widespread vaccination coverage will not be achieved before 2023, if at all’. The widespread and anxiety-generating belief − whether or not backed by scientific evidence − that some new strains of the virus are more contagious or lethal than previous ones may also prompt people to seek an ‘easy fix’ for as long as official channels remain unavailable. Beyond creating a public-health risk, a sizeable black market for vaccines may have wider social impacts. The anti-vax community is likely to trumpet reports of serious health conditions associated with inoculations without necessarily conducting in-depth inquiries into whether the vaccines in question were genuine or fake. Even when they do not cause any health problems, smuggled vaccines whose effectiveness has been compromised may feed conspiracy theories premised on the collusion between money-hungry big pharma companies and depraved political establishments. The veil of confidentiality that largely wraps the contractual documents between governments and pharmaceutical companies is only set to reinforce such ideas. Protecting the integrity of supply chains Urgent and sustained action is needed to address current supply shortages. This is no easy task. Even if leading pharmaceutical companies manage to quickly return to full-speed manufacturing levels, delivery outcome is likely to reduce the overall appeal of the black market only marginally, at least in the short-term. At the same time, requests by some governments for the World Trade Organization to exceptionally suspend the global patent regime in relation to COVID-19 vaccines, which would pave the way for the production of generic products, are met with the resolute opposition of the EU and the United States. But even if the production of generic medicines could run at full steam, the sheer number of jabs needed to ensure global ‘herd immunity’ suggests that the black market is not likely to lose its raison d’être in the foreseeable future. It is thus necessary to double down on efforts to disrupt counterfeit operations and mitigate the risk that genuine products are diverted from supply chains. These often involve several stages and intermediaries. Various traceability solutions, such as radio-frequency identification technologies, do offer important monitoring tools, for instance in the event of a criminal group hijacking a vaccine-transporting truck. But technology only provides part of the answer. Perhaps more than anything else, the recognition is needed that each supply chain has its own characteristics, types and levels of vulnerability. Arguably, for example, it is easier to monitor the movement of vaccines requiring special storage facilities as transportation will only be assured by a small number of highly specialised delivery services. By contrast, vaccines whose conservation is less demanding may be entrusted to a wider spectrum of logistical companies, which may in turn subcontract their services. The more a supply chain is fragmented, the more intermediaries are involved and the more opportunities for diversion are created. Conducting meticulous risk assessments should be the starting point for any serious attempt to protect the integrity of supply chains. Some countries are coming up with imaginative solutions. South Africa has decided to store vaccines in a secret place to prevent theft. But such measures only cover one segment of the supply chain and, as security experts often repeat, a system is only as secure as its weakest link. Hospitals appear to be particularly problematic. In 2014, the academic research centre Transcrime drew attention to the role of organised criminal groups in the theft of medicines from Italian healthcare infrastructure. Recently, Italian investigators have been searching for mismatches between the official records of vaccines delivered to certain hospitals and the number of doses effectively administered. The police are also trying to determine if the vaccine drops left on the bottom of used vials may have been collected for sale on the black market. Reportedly, the administrators of some dark-web market places have discouraged use of their platforms for the sale of illegal vaccines. Paradoxical though it may seem, it appears that this self-restraint is not so much a result of a concern for consumers’ well-being as it is an attempt to avoid heightened media and law-enforcement attention during the current health emergency. Role of corruption and security implications Even if the sale of illegal vaccines does not take root on the dark web, all the conditions are in place for a booming illicit market, both online and offline. In many countries, corruption is often what makes supply chains susceptible to criminal infiltration – whether in the form of bribes offered to employees of manufacturing and transport companies, or collusive relationships between smugglers and hospital personnel (e.g. nurses, doctors, administrative staff), etc. Generally speaking, it can be argued that a black market for vaccines will find particularly fertile ground in countries with weak governmental structures and a poor record of preventing corruption in public life. Without adequate responses, the effects may be felt on many fronts. In addition to being a multiplier factor on infection rates, a flourishing underground economy for vaccines would be a gift to all sorts of extremists bent on spreading conspiratorial narratives, further exacerbating the fractured lines of our polarised societies. Last but not least, a thriving black market in vaccines may have a destabilising effect in institutionally fragile and politically volatile contexts. Where the illicit economy already plays a major role in sustaining local armed groups, the proceeds generated by the sale of illegal vaccines may act as a further catalyst towards the disruption of delicate power balances, the fuelling of active conflicts or the re-igniting of dormant ones. Stefano Betti Deputy Director-General, TRACIT Winston Churchill once said that, “Those who fail to learn from history are condemned to repeat it.” It seems that this adage rings true time and time again.

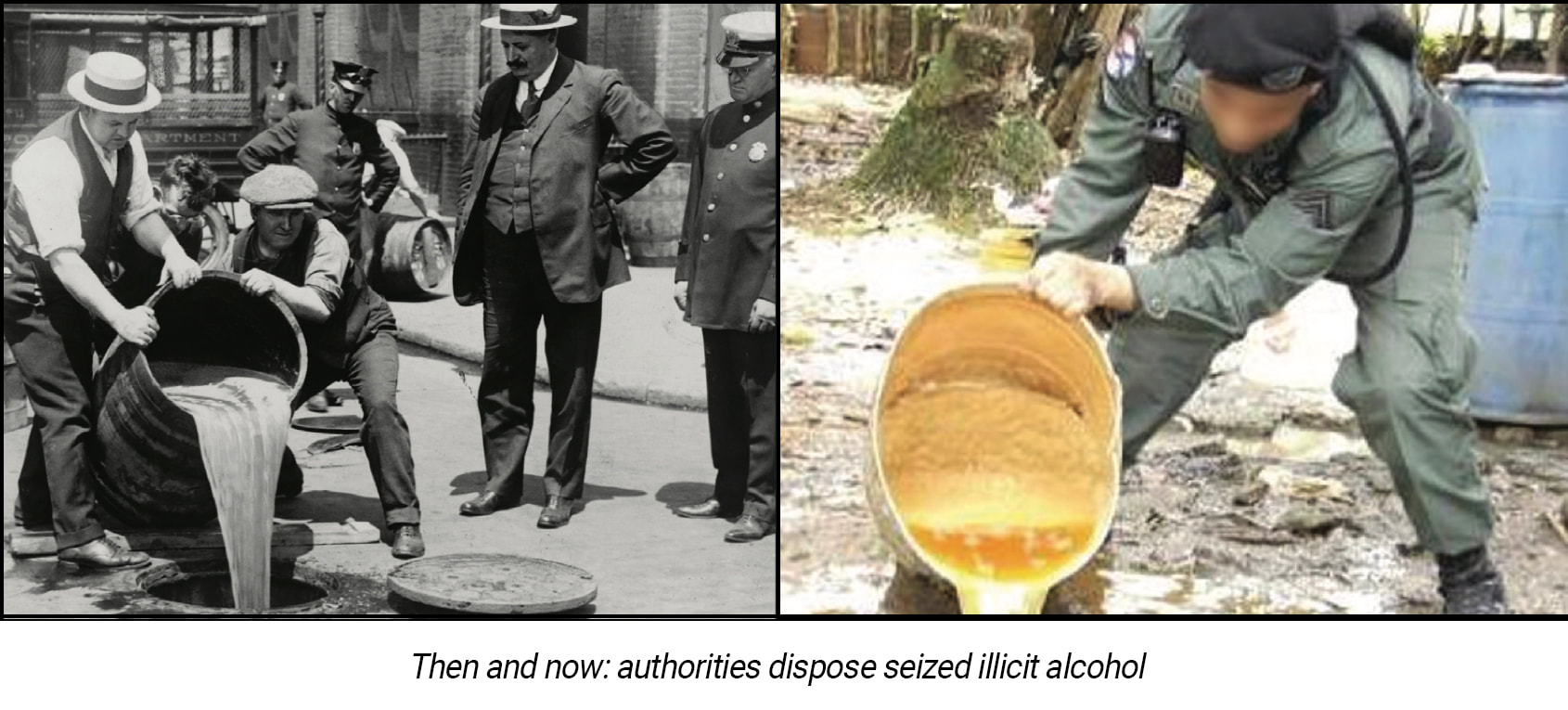

On 12 January 2021 TRACIT released its most recent report on prohibition in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, Prohibition, Illicit Alcohol and Lessons Learned from Lockdown. The report examines the consequences of dry laws enacted by various sovereign states around the world, with a particular emphasis on the countries with the strictest regulations, such as India, Mexico, and South Africa. Drawing parallels to a constitutional amendment that brought the infamous Prohibition to the United States in 1920, the report prompts us to remember a piece of history that we seem to have forgotten in the midst of a pandemic: Alcohol supply restrictions, bans, and outright prohibitions do more harm than good. The Prohibition era in the United States is almost universally regarded as a failed experiment in curbing society’s thirst for alcoholic beverages. In fact, the more the U.S. Government strengthened its dry laws—eventually banning the sale of alcohol altogether—the more the public pushed back, giving birth to a massive black-market and ushering in an era of organized crime and corruption. Chicago, in particular, emerged as a notorious capital for organized crime and illegal speakeasies. Like a snake, the underground market for illicit alcohol has slithered its way back into our lives over a century later—this time on a global scale. The problems we’re currently facing are ones that we’ve seen before—and ones that were easily preventable. The TRACIT report details how instead of avoiding prohibition laws on alcohol during the pandemic, governments around the world did the exact opposite, banning millions of people from access to safe and legitimate products. By sharply reducing supply without a change in demand, governments steered consumers towards unregulated black-markets, inadvertently risking the health and safety of their citizens. In hindsight, governments and lawmakers should have known better. With the publication of this report, we hope to bring some clarity to the problem and provide solutions that will hopefully preclude irresponsible legislation in future. Right now, we governments need to make sure that the growth in illicit alcohol markets does not take root in the long run, and this starts with ramping up enforcement measures to quell any growing illicit trade activity. We can build back better. It’s time we prove Churchill wrong. Selin Hos TRACIT Staff Writer This post was originally published in the Himalayan Times

In March, the Government of Nepal banned imports of international wines and spirits as part of a series of measures aimed at protecting the country’s foreign currency reserves in the face of the COVID-19 crisis. Along with governments worldwide, Nepal is understandably grappling with policies that minimize health risks without side-tracking the economy and destroying job markets. However, it is doubtful the supply restrictions will generate the intended economic benefits and it is almost certain that increased criminal activity and risks to public health will follow. In fact, the last few months have generated several valuable lessons learned from COVID-19 related prohibition laws that were pursued—and then abandoned—in India, Thailand, South Africa, Mexico, and Colombia. In all cases, the laws facilitated growth in illicit trade (and the criminal activity that supports it), exposed consumers to health risks from toxic illicit alternatives, and rapidly drained government revenues dependent on excise tax collections. While emergency restrictions on imports of high-end vehicles might temporarily bolster Nepal’s balance of payments, the fact that imported wines and spirits represent less than 0.2% of the country’s total import value suggests that the ban will have negligible economic impact. On the contrary, the import restrictions may end up costing the country tax revenues and jobs. The heavy taxes on imported wine and spirits generate almost $55 million in the form of excise and customs, much of which will instead be diverted to the criminal black market. Moreover, these lost tax revenues are essential to domestic resource mobilization, enabling Nepal to invest in public services and infrastructure at a time when it is needed most. Looking deeper into the unintended economic consequences of the supply restriction is the impact on Nepal’s vibrant tourism and hospitality sectors. Once international tourists start visiting, post-crisis, they will expect the brands they know and trust to be available. If consumers cannot buy legal alcohol, they will turn to illicit alternatives, with potentially disastrous consequences for Nepal’s reputation as a safe tourist destination. Like other countries in South Asia, Nepal has a significant informal alcohol market that includes dangerous ‘bootleg’ alcohol. According to research by the World Health Organisation and the Nepal Health Research Council, at least 66% of all alcohol consumed in Nepal was either illegal or home-produced, making for an illicit market that is more than twice the size of the legal market. Prohibiting the import of international spirits and wines will only compound this problem, increasing the share of illicit alternatives through smuggling across borders into Nepal and counterfeiting of popular, premium international brands. Spikes in demand for illicit alcohol also present severe health risks to consumers exposed to end-products that do not comply with sanitary, quality and safety regulations and are contaminated with toxic chemical additives. In March, it was reported that police confiscated large quantities of illicit alcohol produced in 38 illegal breweries; and nine people died, and six others became severely ill after drinking illicit alcohol during the Holi festival. Local experts including Dr. Rakesh Ghimire, of the Department of Clinical Pharmacology at Tribhuvan University Teaching Hospital, have expressed deep concern about the deaths that have been registered in just the past few months due to the consumption of toxic alcohol. These horror stories are not new and the public health consequences associated with illicit alcohol are widespread and alarming. More than 100 people died from consuming toxic illicit alcohol in Mexico under COVID-19 prohibitions and the harms of illicit alcohol are so severe that the Health Minister of the Dominican Republic has declared that the consumption of illicit alcohol has caused more deaths than COVID-19 in his country. In just the last year, neighbouring India has witnessed hundreds of deaths associated with toxic, illicit alcohol. The dubious economic benefits of Nepal’s alcohol import restrictions, along with the negative impacts on illicit trade and public health, are a compelling case for the government to reconsider its ban on legitimate imports of international wines and spirits. A better approach would be to ensure the availability and access to legitimate products, enforce health and safety regulations in the sector, and collect the proper tax revenues important to public investment in Nepal. To this end, we support the creation of local private-public partnerships to bring key industry and government stakeholders together to define strategies that can preserve currency revenue needs while securing the legitimate market for alcohol. Jeffrey Hardy Director-General, TRACIT For more information The TRACIT statement on Illicit Trade in context of COVID-19 Product Fraud along with other resources can be found here: /www.tracit.org/covid-19_alcohol This article was originally published by The Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) Perspectives

Over the past few weeks, experts have been examining the ways in which organised crime is exploiting the covid-19 pandemic. Within the EU, for instance, a situational report by the European Union Agency for Law Enforcement Co-operation (Europol) has identified fraud, cyber-crime, counterfeit or substandard goods and property crime as the main areas in which criminal activity has seen an upsurge. By contrast, there appears to be limited discussion internationally about how criminal organisations are likely to profit from the ongoing situation. This reticence persists despite warnings from front line officials such as Italy’s national anti-mafia prosecutor, Federico Cafiero de Raho. In a recent statement he warned that the current social unease provides the mafias with not only economic opportunity but also the prospect of gaining social acceptance. The fact that international agencies such as Europol have not included this issue in their latest reports is easily explained by the lack of available data. While police operations can provide immediate figures on seized counterfeit masks or medications and their value, it is probably too early to measure the extent to which organised crime is making inroads into the lifeblood of national economies. Often the activities do not necessarily constitute criminal conduct per se and only reveal their criminal nature when analysed in retrospect. According to Rosario Faraci, professor of economics at the University of Catania, a good example of this is the practice of complicit suppliers and creditors progressively choking legitimate businesses. It is only when the victim is on the verge of bankruptcy that the criminal organisation presents itself by offering a “friendly” acquisition of the failing business. While the phenomenon has been abundantly studied and monitored in Italy, there is reason to believe that similarly perverse dynamics are at play in other covid-19 affected countries, particularly those with comparable socio-economic conditions. The issue clearly deserves attention at the international level. As the economic lockdown loosens up, many anemic companies will need quick access to money to re-start their businesses. However, the banking system may grant loans on condition of unfeasibly onerous guarantees. At this delicate juncture, several small and medium-sized enterprises may be tempted to turn to unscrupulous money-lenders. Criminal groups benefited from a similar scenario during the 2008 subprime financial crisis. At that time Antonio Maria Costa—then the executive director of the UN Office on Drugs and Crime—argued that proceeds from drug-trafficking were “the only liquid investment capital” available to some banks on the brink of collapse. Accordingly, a vast amount of drug profits—with an estimated worth of £216bn—was injected into the economic system. The difference is that in 2008 the liquidity crisis affected the banking sector: it now affects the “real economy”. This distinction will make little difference to organised crime outfits. On a related note, usury is another highly effective money-laundering vehicle. It is made even more palatable by the fact that, when the loans cannot be repaid, criminal groups can often take direct control of the businesses they were purporting to rescue. History shows a pattern of spikes in usury practices at times of profound economic crisis. Shortly before engaging in the lucrative alcohol-smuggling operations of the Prohibition era, criminal gangs in the US were already accumulating big profits by resorting to “loan-sharking” during the Great Depression. But usury is only one manifestation of a wider problem which is exacerbated in the informal sectors of an economy. For example, by definition people who lose undeclared jobs have no means of applying for any unemployment benefits their governments might provide. The “helping hand” offered by criminal groups may initially appear a gift but will be more akin to slavery in the long term. There are no acts of generosity that come with an expectation of life-long loyalty and subservience. Whether in the form of subsidies, unemployment benefits or state-guaranteed bank loans, many countries are enacting extraordinary transfers of “rescue money” to sustain battered communities. In so doing, it is critical that they modulate these unprecedented injections of liquidity carefully and anticipate how they could impact organised crime. Some resources, in particular, should be used to create or better-equip anti-usury mechanisms. In Italy, the Fund for the Prevention of Usury is a vital safety net relying on the active role of local anti-usury associations. Similar schemes could be implemented elsewhere. It is for each country to determine the appropriate levels of public sector, bank and civil society involvement to prevent organised crime from further encroaching upon the lives and assets of those living in regions with increasingly fragile economies. Stefano Betti Deputy Director-General, TRACIT |

About tracit talking pointsTRACIT Talking Points is a channel we’ve opened to comment on current trends and critical issues. This blog showcases articles from our staff and leadership, along with feature stories from our partners in the private sector and thought-leaders from government and civil society. Our aim is to deepen the dialogue on emerging policy issues and enforcement measures that can be deployed against illicit trade.

Categories

All

Archives

February 2024

|

|

Transnational Alliance to Combat Illicit Trade (TRACIT) is an independent, non-governmental, not-for-profit organisation under US tax code 501(c)(6).

© COPYRIGHT 2024. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. |

Follow us

|